|

Books by

Jeffery Robenalt

|

|

In

July 1845, after the Congress of the Republic of Texas approved

the terms of annexation offered by the United States government,

President James K. Polk dispatched General Zachary Taylor and 5000

Federal troops to the small Texas settlement of Corpus

Christi at the mouth of the Nueces River. According to the Mexican

government, the Nueces was, and always had been, the border between

Mexico and the province of Texas. However, based on the Treaties

of Velasco, signed by Santa Anna after the Texas Revolution,

the Texans insisted the border was the Rio Grande.

In late December, the United States Congress officially recognized

the Rio Grande River as the border. General Taylor then prepared

to move his troops south into the land that stretched between the

Rio Grande and the Nueces known as the Nueces Strip; an act that

would eventually initiate hostilities between the United States

and Mexico. The Texas Rangers were long familiar with the lawless

Nueces Strip, and Captain Jack Hays rode to Corpus

Christi to offer the services of his Rangers to act as scouts

for the American Army, who in 1845 lacked a cavalry branch and depended

on slow-moving, mounted infantry known as dragoons to provide mobility.

|

|

Portrait

of Jack Hays

Wikimedia Commons |

|

While Jack Hays

was presenting his offer to General Taylor, he received word of

a large Comanche war party putting the torch to the settlements

southwest of San Antonio.

Knowing that he could never catch the elusive Comanches by following

their trail, Hays quickly returned to San

Antonio, and after gathering up forty Rangers and a few Tonkawa

and Lipan Apache scouts, rode hard for Enchanted Rock, a well-known

Indian landmark northwest of the old mission town. In this way,

the veteran Captain of Rangers hoped to intercept the war party

before the warriors could escape into the far reaches of the Comancheria.

|

Comanche

Portraits

wikipedia |

|

Hays and his

Rangers reined up at Enchanted

Rock early the following morning only to find that they had

barely missed the Comanches, but the Indian scouts soon found a

fresh trail heading off to the northwest. A severe drought had long

plagued the area, and the scouts were sure that a small lake formed

by the nearly dry Concho River would serve as the only watering

hole in that direction for miles around. The lake stood at the base

of Paint Rock in present day Concho

County. Based on this information, Hays made a fateful decision.

Facing odds of more than ten to one, the Rangers set out to beat

the Comanches to the water.

Forty-two hours and 130 miles of hard, bone-jarring riding later,

Jack Haysís weary Rangers did exactly that, reaching the lake at

1:00 in the morning, well ahead of the unsuspecting Comanches. After

ordering the picketing of the horses to the rear, Hays carefully

concealed his men in a willow thicket along the north shore; the

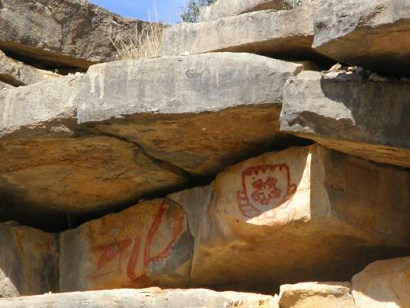

only approach to the water. On the south rim, the face of Paint

Rock rose high above the shimmering moonlit surface of the lake.

|

|

|

As expected,

the war party approached the lake at dawn, thirsty, saddle-weary,

and anxious to rest for the remainder of the day. Hays let the warriors

get as close as possible to the willow thicket before giving the

command to open fire. Smoke and fire billowed out of the willows

with the roar of the Rangersí rifles, and the Comanches fell back

in disarray, carrying off as many of their dead as they could. However,

a few alert warriors spotted the Rangersí trail as they rode out

of range. The tracks clearly showed there were no more than thirty

or forty riders concealed in the thicket. With their superior numbers,

the Comanches believed they could easily overwhelm the Rangers in

the full light of the new day.

The first Comanche attack would come rolling out of the northeast,

ensuring that the blinding glare of the rising sun would shine directly

in the Rangersí eyes. With their short bows, long war lances, and

buffalo hide shields tough enough to turn a rifle ball, the Comanches

presented a fearsome spectacle as they assembled for the charge.

The war chief, feathers and colored ribbons fluttering in the breeze,

lowered his long, scalp-decorated war lance, and the warriors suddenly

broke into a screaming, galloping mass of color.

Hays fired when the Comanches closed to within fifty yards, and

the Rangers quickly joined in with a thunderous volley. Galloping

past the willow thicket, the warriors released a barrage of arrows

as they slid off to the sides of their horses to avoid the deadly

Ranger rifle fire. Circling wide, the Comanches made a second charge

past the thicket before pulling back to regroup for a lance charge

that the Rangers quickly broke with the brutal firepower of their

rapid firing Colt revolvers and muzzle-loading shotguns.

The Comanches made several more gallops past the thicket throughout

the remainder of the day before finally withdrawing to the prairie

and setting up camp for the night. By now they were growing so desperate

for water they were forced to send warriors in relays for more than

twenty miles to get it.

Late the following morning, the Comanches launched a massive attack

in four separate waves, the first waves attempting to get the Rangers

to empty their weapons, so the later waves could close in. A few

warriors in the final wave managed to crash their way into the thicket,

war lances lowered, but they were again blasted off the backs of

their painted ponies by the Rangers superior firepower.

|

|

|

Withdrawing

to the top of Paint Rock, the Comanches spent the remainder of the

day firing arrows high into the air, attempting to arch them into

the willow thicket. The arrows were ineffective from such long range,

but the Ranger rifles managed to chalk up a few more Comanche victims

who carelessly exposed themselves on the rim of the high rock. As

the sun began to set, the frustrated warriors again withdrew to

the prairie, their thirst unquenched.

Early in the morning of the third day the Comanches attacked the

Texans from several different angles at once, forcing the defenders

to divide their fire. Realizing from the diminished volume of gunfire

coming from the thicket that the Rangers were running low on powder

and ball, the war chief took his time, massing his warriors on the

high ground to the northeast for one final attack that would surely

overwhelm the beleaguered defenders.

By mid-morning all was ready and the war chief rode to the front

of his warriors, raising his war lance high and haranguing the Comanches

into making one final supreme effort. Screaming his fury, the Comanche

leader heeled his stallion to a gallop and led what was to be the

final charge at the willow thicket. The Rangers calmly picked out

targets over the sights of their long rifles and took up the slack

in their triggers, waiting patiently for Hays to open fire and swallowing

the fear that churned their bellies as the painted warriors drew

closer.

Hays had been trying to get a decent shot at the Comanche leader

since the fighting had begun, and at less than a hundred yards he

finally got his chance, when the war chief made a fatal mistake

by turning on the back of his galloping pony to urge his warriors

on. As he swung around, the Comancheís buffalo hide shield turned

with him, exposing his right side. Jack Hays chose that instant

to open fire, and the war chief was dead before his body struck

the tall grass of the prairie.

The untimely death of the war chief shattered the momentum of the

charge, and a terrible wail of anguish arose from 600 Comanche throats

as the warriors milled around in front of the thicket. Before the

Comanches could recover their momentum, Rangers up and down the

line opened fire with a rolling volley of thunder. The leaderless

warriors retreated as several more painted ponies were emptied.

Hays ordered one of his men to ride out, rope the war chiefís neck,

and drag the body back to the Ranger lines. This act of defiance

infuriated the Comanches, and they galloped past the thicket one

final time, launching a cloud of arrows before riding away in frustration

to the northwest toward for the Comancheria.

|

|

|

The

Battle of Paint Rock was a resounding victory for the Texas Rangers.

More than 100 Comanche dead lay strewn across the prairie in front

of the willow thicket. Incredibly, only one Ranger had been wounded

in the fighting, and one unlucky horse killed by an arrow launched

from the rim of Paint Rock. With the dawn of the Mexican American

War, Jack Hays would devote the remainder of his Texas Ranger career

serving as a volunteer with the United States Army, riding for both

General Zachary Taylor at Monterey and General Winfield Scott on

the road to Mexico City. Paint Rock was to be his final major engagement

with the Comanches.

Finally, in the absence of official records, some historians have

questioned the truth of the Rangersí victory at Paint Rock, as they

have Jack Haysís efforts at Bandera Pass and his solo fight against

the Comanches at Enchanted Rock. Some have even suggested that Paint

Rock was an attempt to revise history for the sake of tourism dollars

or to ďglorifyĒ the Rangers. However, the Texas Rangers need no

help from me or any other historian to bring glory and honor to

their name. History is, and always will be, an attempt to recount

the distant past, and one manís history is often times another manís

fiction. I choose to believe those like Joe Tom Davis in Volume

IV of Legendary Texans, and Thomas W. Knowles in They

Rode for the Lone Star: The Saga of the Texas Rangers, who believe

in the truth of Paint Rock as I do.

© Jeffery

Robenalt

"A Glimpse of Texas Past"

June

1, 2012 Column

jeffrobenalt@yahoo.com

|

References

for "Paint Rock: The Last Comanche Fight of Jack Hays "

|

|

Austerman,

Wayne R. (2010), Ambush and Siege at Paint Rock, originally

published by Wild West Magazine, published online February 05, 2010,

HISTORYnet.com Weider History Group.

Davis, Joe

Tom (1989), Legendary Texans Vol. IV, Eakin Press, Austin

TX ISBN 0-89015-669-7.

Knowles, Thomas

W. (2009), They Rode for the Lone Star: Saga of the Texas Rangers,

Lone Star Publishing, ISBN 978-09435416.

|

|

|