|

Books by

Jeffery Robenalt

|

|

In

the aftermath of the Great

Comanche Raid of 1840 and the Battle of Plum Creek, Mirabeau Lamar,

the President of the Republic of Texas, was convinced that

the depredations of the Penateka Comanches would continue unless the

savages were thoroughly chastised and taught that such hostile conduct

on their part would no longer be tolerated. The only way to administer

such a lesson was to carry the fight into the heart of the Comancheria.

To accomplish this difficult and dangerous mission, Lamar enlisted

the services of Texas Ranger Colonel John Moore, charging him with

the responsibility of organizing an expedition for the purpose of

attacking and destroying a Comanche winter village somewhere on the

upper reaches of the Colorado River or one of its many tributaries.

If an entire Penateka village could be set afoot and left without

the necessary foodstuffs to survive the winter, the action would clearly

demonstrate to the Comanches that there was no safe haven if they

failed to keep the peace.

Colonel Moore had led a similar expedition to Spring Creek

in the valley of the San

Saba River the previous February, but after an initial success,

the attack on the Comanche village ended in disaster when Moore ordered

an unexpected retreat. In his after action report, the Colonel stated

the retreat had been necessary because of poor visibility and the

need for his men to reload their weapons, however, not all the volunteers

agreed with this assessment.

The Lipan Chief Castro had gone so far as to withdraw his warriors

from the expedition and set out for home. To make matters worse, the

Comanches conducted a well-planned midnight raid and ran off with

more than half of Moore’s horses, forcing many of the men to return

to Austin on foot.

The Colonel was determined such a disaster would not occur again. |

|

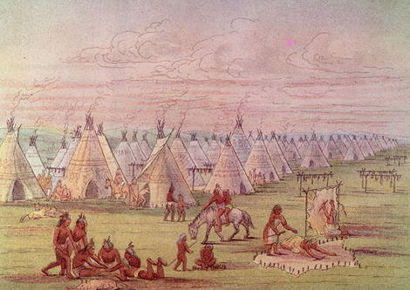

Tipis by George

Catlin

wikipedia |

The

first step in organizing the expedition was to recruit sufficient

manpower, and Moore set about doing this by posting circulars and

placing advertisements in local newspapers throughout the small towns

and widely scattered homesteads of frontier Texas. Considering all

the burning and killing the Comanches were responsible for on the

frontier, it was not surprising that the ads and circulars brought

a prompt response. By early October close to ninety volunteer Texas

Rangers, mostly from Fayette

and Bastrop counties gathered at Walnut Creek near the

new capital of Austin.

Having crossed over much of the same rugged hill country terrain on

his previous expedition, Colonel Moore made the decision to use pack

mules

to carry the expedition’s supplies instead of wagons. He also wanted

to keep from alerting the Comanches to the presence of the expedition

by hunting, so a small herd of cattle

would trail along behind the string of pack mules to serve as a mobile

commissary. |

|

|

On Monday October

5, the expedition, led by Chief Castro and seventeen Lipan Apache

scouts, departed from the camp on Walnut Creek and headed north

toward the San

Gabriel River. Bearing west at the San

Gabriel, the column followed the river's course to its headwaters,

then moved cross country to the Colorado River, thus avoiding the

worst of the hill country. After fording the Colorado, the volunteers

continued northwest, crossing both the San

Saba and Llano

rivers.

|

| Throughout the

expedition’s route, the Lipan scouts spread out, thoroughly scouring

the countryside for any sign of the Comanches, but none was found.

Undaunted, the Rangers pushed further to the northwest. Moore was

one of the first white men to travel so deep into the western reaches

of the Colorado River, and in his later report he stated that

he “found the country rich and beautiful, abundant in game, and

covered with a waving sea of grass broken only by occasional rivers

and canyons, with tremendous vistas.” |

Concho River

Watershed

wikipedia |

As the expedition

drew closer to the Concho River a “blue norther” storm unexpectedly

rolled in and the weather took a severe turn for the worse. Torrential

freezing rain and near gale-force, icy winds plagued the trail, and

it was impossible for the Rangers to stay dry in the miserable conditions.

A number of men became ill as the column continued to plod on through

miles of deep clinging mud and standing water.

One young Ranger, Garrett Harrell, drowned while the expedition was

fording the raging flood waters of the Concho, and Colonel

Moore was beginning to grow discouraged after so many days on the

trail with no sign of the Comanches and little letup in the gloomy

weather. He reluctantly ordered the column to follow the Concho

back to its confluence with the Colorado where he planned to

return to Austin if nothing

turned up and the weather conditions failed to improve. |

Colorado River

Watershed

wikipedia |

However, the

rain abated somewhat as the Rangers drew nearer to the Colorado.

More importantly, the Lipan scouts found tracks of a large number

of unshod horses mixed in with the drag marks of many travois and

the footprints of women and children; clear signs of a village on

the move. The Rangers followed the tracks northwest along the Colorado,

and on October 23, they came across a large grove of pecan trees where

the Comanches had stopped to gather nuts for the winter.

Most of the pecans had been harvested, and with such a heavy load

to carry, the scouts were sure the encampment was not far off. After

ordering the men to take cover in a brushy thicket on the reverse

side of a hill sheltered from the icy blast of the north wind, Colonel

Moore called on his two best scouts to ride ahead. Departing at mid-morning,

the Lipans did not return until near sundown, but they brought welcome

news. The Comanche village was located on a horseshoe bend of the

Colorado less than twenty miles distant. |

|

Comanche Village

by George Catlin, 1834

Courtesy of www.georgecatlin.org |

The news of the

discovery energized the Rangers, and in spite of the miserable weather,

they were eager for an engagement. After eating a cold supper, Colonel

Moore led the column ten miles up the Colorado where the men

secured their small herd of cattle in a mesquite thicket near the

river and continued on for a few more miles.

Halting the march at midnight, Moore ordered the Rangers to dismount

and rest their horses while he dispatched the same two Lipan scouts

to determine the exact location of the village and gather an estimate

of the Comanches’ strength. The Lipans returned a few hours before

sunrise and reported a village four miles upriver on the south bank

of the Colorado with sixty to seventy lodges and an estimated

125 warriors. The column continued its advance for another two miles

where they secured their pack animals in a wooded hollow and waited

for daylight.

Near sunrise on October 24, Colonel Moore gave the long-awaited order

to mount and move forward. As the Rangers approached the sleeping

village, Lieutenant Clarke Owen, recently arrived at Austin

from Mississippi, was ordered to ford the Colorado below the

camp with the Lipan scouts and be prepared to deal with any Comanches

who managed to make it across the river. Captain Thomas Rabb from

La Grange and his men

would form up on the right, Captain Nicholas Dawson from Bastrop

and his men would be on the left, and Colonel Moore would ride with

the men of Lieutenant Owens and command from the center.

The Rangers moved to within two hundred yards of the encampment without

being detected and slowly went on line; only the fog-muted jingle

of harness and the soft squeaking of saddle leather disturbed the

deathly silence of the early morning. When all was in readiness Colonel

Moore gave the signal and the entire command started forward at a

walk, quickly moved into a trot, and finally broke into a thundering

gallop. |

|

Comanche Warriors

by George Catlin

Courtesy of www.georgecatlin.org |

The Comanches

were taken by complete surprise, stumbling out of the snug warmth

of their buffalo robes only to be greeted by the howling screams of

the Rangers and the hammer-like pounding of countless hooves. Nearly

naked and weaponless, the Indians fled for the perceived safety of

the ford on the Colorado.

The rangers brought down a virtual hail of gunfire on the retreating

and confused Indians as they galloped into the village unchallenged.

Halfway through the scattered buffalo-hide lodges Moore called for

the men to rein in so they could dismount and reload. After quickly

reloading, the Rangers continued to fire until the barrels of their

long rifles were smoking hot. Many Comanches were killed before they

reached the Colorado, and a large number of others were brutally

gunned down as they attempted to flounder across the ford, their bodies

swirling away with the current.

The Rangers advanced to the river in an orderly fashion and continued

to fire at the fleeing Comanches, hitting many of them as they emerged

from the river on the opposite bank. The Comanches who were fortunate

enough to run the deadly gauntlet of fire from the village and safely

reach the far bank fled across the open prairie only to be ridden

down by Lieutenant Owens and his Lipans who had been eagerly awaiting

just such an opportunity.

The scene was one of carnage. Bodies of dead, dying, and wounded Comanche

men, women, and children lay sprawled across the village and both

banks of the Colorado. Although an honest effort had been made

by most of the Rangers to spare the lives of the women and children,

a good number of them had been killed or wounded in the confusion

of the fight.

Colonel Moore later reported that forty-eight Comanches had been “killed

upon the ground, and eighty killed and drowned in the river.”

Many of the Rangers believed this estimate was too low. Thirty-four

Comanche prisoners were taken during the fight. None of the Rangers

were killed and only two suffered minor wounds. |

|

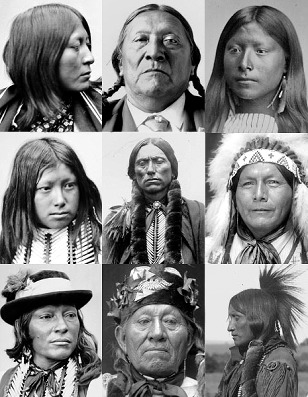

Comanche

Portraits

wikipedia |

|

The

victory on the Colorado was undoubtedly the most severe punishment

the Comanches had ever received at the hands of the Texas Rangers.

In addition to the many casualties and prisoners the Indians suffered,

all the property and food in the village was either confiscated

or destroyed, including much of the loot that had been carried away

from the raid on Victoria

and Linnville.

More than five hundred Comanche horses were also rounded up.

The Rangers returned to Austin

on November 7, with the welcome news of their victory, and the grateful

citizens held a dinner and celebration in their honor. The power

of the southern Penateka Comanches was forever broken, and although

they remained a nuisance, they were never able to fully recover

from the results of the devastating defeat on the Colorado

coupled with the losses they had suffered at the Council

House fight and Plum

Creek. However, the Texans and the northern Comanche tribes

had not yet come into meaningful contact, and the struggle for control

of the western frontier would continue for many more years.

© Jeffery

Robenalt

"'A Glimpse of Texas Past"'

January

25, 2011 Column

|

|

|