|

|

In

the spring of 1840, the Navy of the Republic of Texas was immersed in a political

battle between President Mirabeau Lamar and his arch-enemy, former president Sam

Houston, currently serving as a member of the Texas Congress. The Congress,

led by Houston, had already

dismantled the Texas Army in an effort to curtail Lamar’s free-spending, expansionist

policies, and now they were set on dealing with the Texas Navy in the same manner.

Into the midst of this acrimonious struggle, stepped a 28-year-old naval first

lieutenant, Edwin Ward Moore, fluent in Spanish, and with 12 years experience

in the American Navy.

In 1838, a United States squadron of warships, including

Edwin Moore’s sloop-of-war Boston, anchored in Galveston Bay. Lieutenant

Moore, whose brother already resided in Texas, became

intrigued with the efforts of the new Republic to start a navy from scratch. Since

prospects for promotion were dim at best in the U.S. Navy of the day, which was

both small and out-of-date, Moore decided to take a risk and offer his services

to the Republic of Texas. In 1839, he resigned his American naval commission and

accepted an appointment as commodore of the new Texas fleet. The majority of the

other officers who served in the fleet were also recruited from the U.S. Navy. |

|

Naval

Scene from Republic

Texas 1838 Currency

Wikimedia Commons |

The first task for

the newly promoted Commodore Moore and his officers was to enlist the sailors

and marines required to man the fleet. To accomplish this task, Moore traveled

to New York, where he set up a recruiting office at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, offering

both adventure and prize money for all men who joined the Texas

cause. He soon had the seamen he required, only to return to Texas

and be caught up in the squabble between Lamar and Houston.

However, Moore could plainly see that Lamar’s proposed mission to Mexico had public

support, and being unfamiliar with the highly partisan politics of the Republic,

he disregarded the strong opposition to his plans by the Houston

faction.

Eager

to apply pressure to the ongoing secret negotiations between Texas

and Mexico, Commodore Moore set sail in June 1840, on the flagship Austin,

accompanied by the steamship Zavala and three schooners. Moore had little

faith in the peace negotiations, and he was determined to deal a blow to Mexico

that would bring the Mexicans to heel and force them to recognize the independence

of Texas. In support of this goal, he established

a blockade of the Mexican coast off the port of Tampico, stopping all incoming

and outgoing ships.

By

fall, it was obvious that the peace negotiations had failed, and with the fleet

desperately low on food and fuel, Moore was forced to choose between taking action

and sailing home. He chose action, sailing the Austin, the Zavala,

and the San Bernard ninety miles up the Tabasco River to the provincial

capital of San Juan Bautista, where he negotiated a deal with the Yucatan rebels,

who were locked in a struggle with the Mexican government for their own independence.

The agreement called for Moore to assist the rebels in capturing the capital in

exchange for $25,000, but when the city fell without a shot being fired, the Texans

had to seize two rebel ships and hold them for ransom before receiving their money.

The fleet sailed for Texas in January 1841. |

|

San

Bernard (left) and San Jacinto (right) Schooners-of-war

Photo courtesy Ken

Rudine, March 2010 |

Zavala

(left) and San Antonio(right) Schooners-of-war

Photo courtesy Ken

Rudine, March 2010 |

Upon his return to

Galveston,

Commodore Moore was greeted with the news that Great Britain had formally recognized

the Republic of Texas. Moore wanted to return to sea immediately and continue

to pressure Mexico, but during a brief meeting with Lamar, the President decided

it would be best to wait and allow Britain to try and negotiate a settlement between

Mexico and Texas. However, instead of laying up his

ships for repair and discharging most of his seamen as Lamar had first suggested,

Moore persuaded the President to keep the Navy busy by conducting a survey of

the Texas coast. The survey

was a complete success, resulting in the first accurate navigation charts of the

Gulf of Mexico. With the use of the new charts, shipping losses dropped dramatically

and insurance rates fell, providing a boost to the Texas

economy.

Meanwhile,

Mexico had broken off negotiations, and President Lamar and his Secretary of State,

Samuel A. Roberts, had become disenchanted with the prospects for peace with the

government of Santa Anna. As a result, Lamar launched his ill-fated expedition

to Santa Fe and entered into secret negotiations with Yucatan to form an alliance

against Mexico. In 1838, an insurrection had begun in Yucatan. The rebels were

deeply dissatisfied with the dictatorial methods of Santa Anna, and in 1840 the

local assembly, like its new Texas ally, had declared

independence and drafted a constitution based on the Mexican Constitution of 1824.

In September 1841, a deal was struck between Yucatan and Texas,

whereby Yucatan agreed to pay Texas $8000 a month

for the use of three ships to defend its coastline against Mexican raiding. All

proceeds from any prize ships taken in the operation would be split. Commodore

Moore was given command, with orders to capture Mexican towns and demand ransom

payments for their return. In order to enforce payment, Moore was authorized to

destroy public works and seize public property. However, speed was of the essence

if the operation was to be implemented. Sam

Houston had just been reelected President of the Republic, and Lamar and Moore

feared that, if given the opportunity, he would cancel the agreement with Yucatan

as soon as he took office.

On December 15, two days after being sworn

in as President of the Republic, Sam

Houston issued an order canceling the Yucatan operation, but the order arrived

too late. The Austin, the San Antonio, and the San Bernard

had already set sail for Sisal, Yucatan. Commodore Moore was fully aware that

his mission did not have the approval of President Houston. After his departure,

he wrote to his good friend, General Albert Sydney Johnston, that he would most

likely be recalled at the earliest opportunity and subjected to vicious political

attacks by the supporters of Sam

Houston.

When the fleet arrived in Sisal, Moore discovered that Yucatan

was in the middle of negotiations with Mexico to end the rebellion. Realizing

that an end to the hostilities would threaten the security of Texas,

he persuaded the Yucatan officials to keep their agreement with the Texas Navy

until they were certain that Mexico, and more importantly the wily Santa Anna,

were sincere about wanting a peaceful settlement. He immediately sent the San

Antonio back to Texas with a detailed report

for President Houston, and included an urgent request that the steamship Zavala

be repaired as soon as possible and sent south to reinforce the Texas fleet. Unfortunately,

Texas had only a small navy yard and no one with

the technical expertise to repair the steamship, and it was never sent.

Continuing

the operation, Moore captured several Mexican ships, before receiving news that

convinced him he was following the right course. Word reached the fleet that the

Texas prisoners, taken as a result of Lamar’s

Santa Fe expedition, had been brutally forced marched the entire 1500 miles

to Mexico City, where the few survivors had been thrown into prison. To make matters

worse, Santa Anna had ordered an incursion into Texas

by General Raphael Vasquez that resulted in the brief occupation of San

Antonio. Unknown to Moore, President Houston had issued orders to maintain

the blockade of the Mexican coast, retroactively approving the fleet’s actions.

Moore continued his depredations of Mexican shipping in and around the vital port

of Veracruz, until April 1842, when low on money and supplies, and with the men’s

terms of enlistment running out, he sailed for New Orleans. |

|

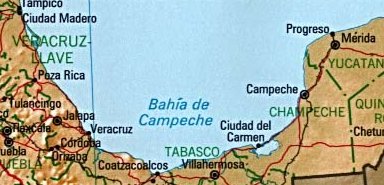

Bay of Campeche

Wikimedia Commons |

While in New Orleans

tending to the repair and refit of his ships, Commodore Moore received orders

to return to Texas. In May, Moore met with President

Houston in Galveston,

where he learned that Houston planned to withhold the $20,000 Congress had appropriated

for the Texas Navy. Moore failed to understand Houston’s

motives. Publicly, the man was calling for volunteers to avenge the Santa Fe disaster

and the sack of San Antonio by Mexican troops, but privately, he appeared to favor

a different course. The President had rescinded his blockade order just nineteen

days after sending it to Moore, and then after telling Moore he wanted him to

lead an invasion of Tampico, he had failed to call Congress into session in time

to approve it.

By July, Moore had come to despise Houston’s

constant wavering, accusing the President of “humbug” and considering resigning

“in disgust,” however he later wrote that he “still hoped to redeem the enterprise

from failure, which was so important to the salvation of my country.” Relying

on the hope of prize money and help from Yucatan, Moore used his own credit to

equip and provision the fleet. While back in New Orleans, Moore received conflicting

orders. He was told to sail at once and begin to prey upon Mexican shipping, hoping

that his actions would force the Mexicans to resume negotiations. He was also

told to bring the fleet back to Galveston,

if he could not find the additional funds necessary to make the ships seaworthy.

While

contemplating which course to follow, Moore received word from his friends in

Texas that Houston

was planning to sell the Texas Navy, and that the President had delivered a secret

message to Congress accusing the Commodore of malfeasance with naval funds. Moore

had incurred more than $35,000 in personal debt attempting to keep the fleet at

sea, and although he was outraged by Houston’s

accusations, he still wanted to continue the mission. Once again the government

of Yucatan came to Moore’s assistance, offering an agreement similar to the one

they had made with President Lamar two years previously. For a payment of $8000

a month, the Texas Navy would break the Mexican blockade and continue to patrol

the coast off Yucatan until it was free of Mexican warships.

Moore quickly

provisioned his ships and made ready for sea, gathering men from wherever they

could be found, including the local jails and workhouses. By mid February, the

fleet was ready to sail, but before the ships could weigh anchor, two of Houston’s

commissioners, Colonel James Morgan and William Bryan, arrived with orders to

take control of the navy and sell the ships. Stating the he was under an obligation

to Yucatan, and that his ships were in good repair and ready for action, Moore

defied the Commissioners and somehow persuaded them to allow him to sail to Galveston

and answer President Houston’s charges in person. Bryan decided to return to Texas

for further instructions, but Colonel Morgan actually joined Moore, writing that

the ships were in “apple pie order” and the crews “bully.”

The Austin

and the Wharton sailed on April 15, 1843, and with Morgan’s concurrence,

set a course directly for Yucatan, bypassing Texas. On the morning of April 30,

the Texas vessels and two Yucatan ships, along with five small gunboats, engaged

six Mexican vessels, including the new steamships Mocteczuma and Guadaloupe.

The fighting was hot and heavy, with one broadside after another exchanged throughout

the course of the morning, but the battle proved inconclusive. The Mexicans withdrew,

but later in the day, with the Texans now nearing the port of Campeche, the battle

resumed. During the heavy fighting that followed, the Texans suffered only two

killed and three wounded, while the Mexicans lost twenty-one killed and thirty

wounded.

Commodore Moore spent the next two weeks stalking the Mexican

steamships, and on May 16, engaged them once again. At one point in the battle,

Moore sailed the Austin directly between the Mocteczuma and the

Guadaloupe, closing with the Mexicans and raking their decks with several

thunderous broadsides. The Austin was badly damaged in the brawl, with

three killed and twenty-one wounded, but the Mexican steamships both suffered

serious damage with 183 killed. The battle would go down as the only victory in

history of sail over steam. Colonel Morgan later landed at Campeche where he received

a letter from President Houston telling him to “by all means have the Commodore

‘yoked’ and manacled, if possible.”

Houston

had issued a public proclamation on May 6, in Texas,

denouncing Moore and charging him with mutiny, treason, and piracy. In the proclamation,

Moore was further charged with disobedience and violation of Texas law. In addition,

the Commodore was suspended from duty and ordered to return to Texas

immediately for court-martial. When Morgan reached Moore with the news on June

1, the two men decided to make for home where they would hold Houston

to his word and demand a trial in which the Commodore would have an opportunity

to explain his actions and clear his good name.

On July 14, Commodore

Moore arrived in Galveston

where he received a hero’s welcome. As far as the public was concerned, Moore

had defended Texas and avoided a potential disaster. The people burned a figure

of Houston in effigy during the celebration. Sam

Houston, however, was unmoved by Moore’s public support. The Texas seamen

were dismissed, Colonel Morgan was fired as a commissioner, and Commodore Moore

was given a dishonorable discharge from the Texas Navy.

After publishing

a 200-page pamphlet documenting his actions, a Congressional investigation found

that Moore had been illegally dismissed and, therefore, entitled to a court martial.

The trial lasted 72 days and in the end, Commodore Moore was convicted of only

four minor counts of disobedience. President Houston, along with the citizens

of Texas, considered the verdict a complete victory for Moore, and he angrily

vacated the findings of the court.

© Jeffery

Robenalt

"A Glimpse of Texas

Past"

December 2, 2012 Column

jeffrobenalt@yahoo.com

References

> |

| Books

by Jeffery Robenalt - Order Here > |

References

for "The Yucatan Adventure" |

Dienst, Alex (1987);

The Navy of the Republic of Texas, 1835-1845; Fort Collins, Colorado: The Old

Army Press (originally published 1909). Douglas,

C.L. (1973); Thunder on the Gulf; Fort Collins, Colorado: The Old Army Press (originally

published 1936).Hill,

Jim Dan (1982); The Texas Navy: In Forgotten Battles and Shirtsleeve Diplomacy;

Austin: State House Press (originally published 1937).Jordan,

Jonathan (2006); Lone Star Navy: Texas, the Fight for the Gulf of Mexico and the

Shaping of the American West; Washington D.C.: Potomac Books; ISBN 973-1-57488-512-5.

Meed, Douglas

(2001); The Fighting Texas Navy, 1832-1843; Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press;

ISBN 973-1-55622-3.Wells,

Tom Henderson (1988); Commodore Moore and the Texas Navy; Austin, TX: University

of Texas Press; ISBN 973-0-292-71118-1.

On

Line Addresses The

Handbook of Texas Online: Texas Navy.The

Portal to Texas History: Texas Navy Texas

State Library and Archives Commission: https://www.tsl.state.tx.us/exhibits/navy/moore.html.

| |

| Book Hotel Here

- Expedia

Affiliate Network |

| Books

by Jeffery Robenalt

Order Here | |