|

Sam

Houston (1793-1863) was the first elected

President of the Republic of Texas. At six feet, three inches tall,

he was an imposing figure, a man of character, strong will and courage.

Houston was a

United States Senator, governor of Tennessee, lawyer, politician,

land speculator, drunk, general of an army, poet, father, husband,

lover—and twice President of the Republic that he helped create.

In 1833 Antonio López de Santa Anna was elected President of Mexico.

He was also the commander of Mexico's army. In March of 1836 he led

a force of 1,500 soldiers to Bexar (San

Antonio) to subdue the Texas rebels, a force comprised mostly

of former American citizens, Hispanic ranchers and farmers who had

joined the revolution for independence. Six months earlier, General

José Urrea's forces defeated the rebels at Goliad,

mostly farmers and ranchers who surrendered when promised fair treatment.

Although Santa Anna ordered them murdered, about thirty escaped while

their comrades were shot down in cold blood.

When Santa Anna's forces arrived in Bexar, he found William Barrett

Travis and less than 200 militia men fortified in the Alamo.

They'd been ordered by Houston

to abandon the site and join him, but they'd refused. Some think that

was a strategic error. Travis and his men fought as bravely as any

could. They killed or wounded about 600 Mexican soldiers, but were

not victorious. Their defeat was costly to the Texans, weakening Houston’s

already small army.

Houston had a

plan of defense which most Texans did not support—one of waiting and

running ahead of a much superior force than they had until he was

in a position to win a battle. Houston

was determined to lead the Mexican Army on a wild goose chase, utilizing

a "scorched earth campaign" beyond their supply lines, stretching

them out geographically and logistically until he could fight them

at a time and place that he chose—one where he would still have an

army after the battle was over. Dead men can’t win wars. Houston's

men hated him for refusing to fight and many deserted, calling him

a coward because of his policy of running away, but run he did.

Houston's forces

ran until the Mexicans began to straggle. When he made his camp beside

the Rio San Jacinto, Houston realized he was facing a forward element

of the Mexican army, but not the whole army. The Mexican force was

much larger than his small army by a wide margin, but not so large

as to make it impossible for him to fight them. If the enemy had been

too strong, he would not have engaged them. Santa Anna had about 1,500

men, while Houston had about 800, but Houston realized that he had

a chance to win the fight. Morale was low, so he had to take the chance

as his men were losing confidence in him.

Though he didn’t know it, Houston

was on the verge of winning the war. On April 21, 1836 he addressed

his men, asking them if they wanted to fight today. The surprised

and disheartened men, sick to death of retreating, cheered when they

understood what he was about to do. Though outnumbered and outgunned,

this rag tag army of Texan and Mexican farmers and ranchers, store

merchants, and every other kind of civilian, attacked Santa Anna's

superior force. Mounted on his horse, Houston

led the charge. He was not a general who stayed behind, directing

his men from a place of safety. He was in front of his men at all

times, inspiring them to charge and charge they did. Houston

was on his third horse as two others had been shot out from under

him. He stayed in the fight even though his boot was full of blood

from a shattered ankle. Houston

and his men killed about 600 Mexican soldiers, captured over 700,

and chased the rest out of the area on foot, many drowning in the

nearby swamps.

Houston’s casualty

list was less than a dozen dead and less than two dozen wounded which

truly amounted to a miracle of generalship if there ever was one.

Resupplied with ordinance and supplies captured following the battle,

Houston and his

small army were able to continue their campaign. The Texan forces

were stronger and the Mexican forces weaker after this battle. Compare

San

Jacinto to the Alamo

and you know what a victory looks like and what a defeat looks like.

If that wasn't enough of a victory, the next day brought the Texans

an even greater victory—they captured General Santa Anna, the president

of Mexico. Incredible as that seems, the dictator who envisioned himself

the best general in the entire world was actually leading a forward

group of soldiers. He was the one man in the entire world who could

end the war, which he wanted to do to save his own neck, now in the

hands of the men whose farms he had destroyed. These men were the

survivors of other battles or relatives of those Santa Anna had murdered,

wives and children he had caused to be killed or raped and robbed.

There was not one man in all of Texas

who wouldn't have wanted to tear Santa Anna to pieces with his bare

hands. Houston’s

men wanted to hang Santa Anna from the nearest tree and Santa Anna

knew it. Nothing stood between he and that last step off the back

of a wagon with a rope around his neck except for one wounded man—Sam

Houston. Houston knew what an asset they had and he stopped his

men. They didn’t like it, but they obeyed because of the victory he

had brought them.

What does Sam

Houston have to do with the California Gold Rush of 1848-49? |

|

| USPS Stamp Commemorating

the 1849 Gold Rush |

Gold Rush Miners

Photo courtesy U of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

What does

Sam Houston have to do with the California Gold Rush of 1848-49?

Following the Mexican defeat at San

Jacinto, Sam Houston

and General Santa Anna signed the Treaty

of Velasco where it was agreed that Mexican troops would be withdrawn

from Texas soil and that the Rio Grande River would be the boundary

between Mexico

and the new Texas republic. In exchange for safe conduct back to Mexico,

Santa Anna agreed to "lobby" his government for recognition of the

new republic of Texas. However, that didn't happen. Instead, Santa

Anna was held as a prisoner of war for six months, and then taken

to Washington, D.C. By the time he returned to Mexico

in early 1837, Texas independence was a fait accompli, although Mexico

did not officially recognize the new republic until the Treaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2, 1848 (the peace treaty

ending the Mexican-American War of 1846-48.)

On December 29, 1845, the Republic of Texas was annexed to the United

States, becoming the 28th state in the union. As a result, the United

States "inherited" the territorial claims of the former republic,

including the disputed area between the Rio Grande and Nueces Rivers

(which led to the Mexican American War that was concluded by the Treaty

of Guadalupe Hildalgo.) The first of five laws passed as part of the

Compromise of 1850 set the present boundaries of the state of Texas

in return for payment of $10 million, the amount of debt accumulated

by the Republic of Texas during its struggles with Mexico. |

|

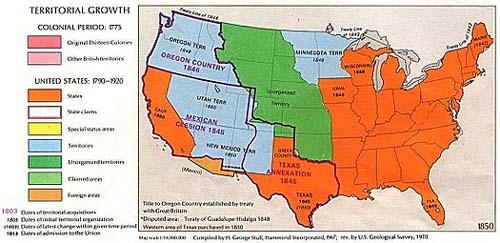

U.S. Territory

in 1850

Wikipedia |

|

The second law

passed as part of the Compromise of 1850 provided for the organization

of two new territories: New Mexico and Utah. The land transferred

from Mexico to the United States (referred to as the Mexican Cession

of 1848) included all of present-day California, Nevada, and Utah,

most of present-day Arizona, the western half of present-day New Mexico,

part of present-day Colorado, and a small part of present-day Wyoming.

The land for the Utah Territory had been claimed by the Republic of

Texas and included the eastern half of present-day New Mexico, southern

and western parts of present-day Colorado, and parts of present-day

Kansas, Oklahoma, and Wyoming.

The third law passed as part of the Compromise of 1850 allowed for

California's admission to the Union on September 9, 1850. The Gold

Rush in 1848-1849 brought enough people into California to make it

eligible to become a state.

In some ways, Sam

Houston was the "the father of his country", the Republic of Texas.

He led an army to victory over Mexico

and not only gained independence for the new republic, but ultimately

enlarged the United States with the annexation of more than 500,000

square miles of land.

At the end of his life's journey, Houston

was lying in his bed, unconscious, while his wife Margaret read to

him. She later wrote, “His is lips moved” and she heard him say, “Texas—Texas—Margaret"

— And he left us." The doctor said he died of pneumonia, but I think

it's more likely that he died of a broken heart as he watched American

fathers and sons kill each other and tear his country and Texas to

pieces for no sensible reason. |

©

Frank W. Lewis

They Shoe Horses, Don't

They? April

11, 2011 guest column

Frank W. Lewis’ name is engraved at the state capitol in Carson City

as one of Nevada’s leading prospectors.

His latest book is The Gold Rush: 1847-1849. Visit the author

at www.rumpah.com

and join his fans on Facebook. |

|

Resources:

The Raven: A Biography of Sam Houston [a Pulitzer Prize winning

biography] by Marquis James, University of Texas Press (1988). The

conclusions and interpretations of the words quoted in the last paragraph

are those of Frank W. Lewis, the author of this article.

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, articles: the "Battle of the Alamo,"

the "Battle of San Jacinto," the "Treaty of Velasco," the "Treaty

of Guadalupe Hildalgo," and the "Compromise of 1850" (including the

"Map of Territorial Growth" illustration.) |

|

|

|