|

Books by

Jeffery Robenalt

|

|

| Not

all Texans were in agreement about secession from the Union and many

more were opposed to the Confederate Conscription Act. Historians

estimate that nearly 30 percent of the Texas population had Unionist

sentiments, though the great majority, like Sam

Houston and James

Throckmorton, remained loyal to Texas.

However, as events would bear out, many dissenters paid a heavy price

for expressing their doubt of the Southern cause and their opposition

to the draft. Kangaroo courts were commonplace across the state and

vigilante justice was administered without mercy. Generally the punishment

meted out by the vigilantes was to burn the victim’s house or business

or to apply a painful coat of tar and feathers, but even murder and

lynching were far from uncommon. By 1863, most dissenters had either

learned to keep their opinions to themselves or had packed up and

fled south to Mexico or west to California. |

|

|

Robert

Edward Lee

General of the Confederate Army

Wikimedia Commons |

After April

1862, much of the dissent throughout the South centered on the new

Conscription Act and Texas was no exception. An incredible number

of Texans had already volunteered for service with the Confederate

army, but the ongoing slaughter in the east required a constant flow

of manpower. To fill this void, General Robert E. Lee was instrumental

in securing the passage of the Confederate Conscription Act, though

the concept of the draft law was just as unpopular in the south as

it was to later prove in the North. The Texans who were eager to fight

had long since volunteered to serve, and there was insufficient manpower

remaining in the state to protect the frontier from the depredations

of the Comanches and maintain the agrarian economy.

To make matters worse, the draft law was both poorly drawn and even

more poorly executed. Discrimination was rampant, and the law was

applied unevenly. Even petty officeholders were exempt, as were all

men “considered indispensable.” This poorly drafted phrase would be

the cause of much abuse. Some exemptions like those for doctors and

men assigned to frontier defense were sensible, but any man of means

was permitted to pay a poorer man to stand in his place. Finally,

the fact that the “indispensable” provision was interpreted to include

almost all men of property was bitterly resented by both the civilian

population and most of the men in the army—volunteers included.

|

|

|

Confederate

General Paul Octave Hebert

Wikimedia Commons |

Thousands of

angry citizens across the state attended protests of the draft law.

Many of the protests were near riots, and in May General Paul Octave

Hebert, the recently appointed commander of the Military Department

of Texas, declared all of Texas to be under martial law. Hebert was

a West Point graduate who had spent much of his service in Europe

where he developed a continental military style that Texans found

displeasing in the extreme. Writer Thomas North described him as preferring

“red-top boots, a rat-tail moustache, fine equipage, and a suit of

waiters . . . He was too much of a military coxcomb to suit the ideas

and ways of a pioneer country.”

General Hebert set about establishing martial law and administering

the draft by appointing local provost marshals and providing them

with virtually unlimited authority. Both Governor Lubbock and the

Texas Supreme Court upheld Hebert’s actions, thus there was no appeal

from the decision of a provost marshal. They were answerable only

to General Hebert. Ruthless enforcement of the draft and the unpopular

property confiscation codes drove some parts of the state into actual

resistance and protests were commonplace. Age was always a question

where birth certificates did not exist and records of any kind were

rare. Provosts, often young and inexperienced second lieutenants,

decided who was old enough to conscript and young boys who resisted

were hunted down without mercy.

The taking of property under the confiscation codes may have aroused

even more ire than the draft law. Under the codes, the property of

all persons adjudged to be “disloyal” was subject to sequester. Of

course, the local provost marshal had the power, if not the wisdom,

to decide the question of loyalty. There were blatant cases where

the lands of men who were imprisoned in the North were confiscated

without the right of appeal, and even the lands of men who happened

to be fighting for the Confederacy in another state were wrongfully

seized. Those who were identified as loyal to the Union suffered the

worst of all. On many occasions, the lands of individuals who expressed

Unionist sympathies were forfeit even when it could not be proven

that they had committed an overt disloyal act.

Dissent

went far beyond mere protest in north Texas where many immigrants

from the North had established prosperous farms and also in the German

counties of the Texas

Hill Country, especially Gillespie,

Kerr, and Kendall.

Many of the settlers in these counties were German intellectuals,

Freethinkers who came to Texas in 1848 after attempting to stage a

revolution. When the revolution failed, their choices were either

immigration or prison. Of course such people opposed slavery. Only

33 slaves resided in Gillespie

County in 1860. However, the Germans had refrained from public

protest until secession finally forced their hand. Gillespie

County’s strong opposition to secession—evidenced by a vote

of 400 to 17 against—was not based solely on a hatred of slavery.

The Hill Country

was on the edge of the frontier, and the withdrawal of the U.S. Army

meant renewed attacks by the Comanches.

The Confederate government in Austin

did virtually nothing to protect the Texas frontier, and the state

militia was of little help. Moreover, the hasty formation of the militia

gave rise to some units that were more outlaws than soldiers, using

the guise of the Confederacy to rob and terrorize the remote ranches

and farms along the frontier. The Germans called these outlaw bands

“Die Hagerbande” or the Hanging Bandits. With their homes and communities

at risk, the Germans were not only opposed to the war on principal,

but were also determined to resist conscription out of the need for

self-defense. To meet this need, they organized their own militia

called the Union Loyal League. |

|

|

Confederate

General Hamilton P. Bee

Wikimedia Commons |

|

The Confederate

government in Austin sent

notorious Confederate irregular Captain James Duff to Fredericksburg,

the county seat of Gillespie

County, in April 1862 to enforce conscription and disband the

Union Loyal League. Duff, a man of questionable character, had been

dishonorably discharged from the U.S. Army. He demanded that all

Unionists take an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy or be declared

traitors, stating that “the God damn Dutchmen are Unionists to the

man,” and “I will hang all I suspect of being anti-Confederates.”

Duff’s actions caused the Hill

Country to erupt in turmoil, and General H. P. Bee, the commander

of South Texas, virtually declared war on the entire area, causing

hundreds of men to flee, some into the waiting arms of the Union

army.

In early August, 1862, Fritz Tegener, a German language scholar,

led sixty-five dissenters, men and boys, south from Fredericksburg

and Comfort

toward the Rio Grande. Once they crossed into Mexico, the Germans

hoped to catch a ship for Union-held New Orleans. They were armed,

but their immediate purpose was to flee the state, not fight the

Confederacy. However, when Duff learned of the flight he sent Lieutenant

C.D. McRae and ninety-four men after the Unionists. Not expecting

close pursuit and with little military experience, the Germans set

up camp on the Nueces River about twenty miles from Fort

Clark in present-day Kinney

County without choosing a good defensive position or posting

a guard. McRae and his men came upon the camp late in the afternoon

of August 9, but waited until early the following morning to launch

their attack.

|

|

Nueces River

between La Pryor

& Uvalde,

TX

July 2010 photo courtesy Billy Hathorn, Wikimedia Commons |

Firing began

an hour before sunrise, as the confederates swept down on the sleeping

camp. The fighting was hot and of the Unionists, 19 were killed—some

trampled to death in their bedrolls—and 9 were wounded. Twenty-three

of the remaining Germans escaped into the surrounding hills, but 8

more were killed by the Confederates on October 18, while trying to

cross the Rio Grande. The battle was also a minor disaster for McRae,

who suffered 12 killed and 18 wounded, including himself. McRae ordered

his men to set up camp and tend to their wounded. At first, the Confederates

also cared for the Germen wounded, but later in the afternoon the

wounded Unionists were carried outside the camp and executed.

Both contemporary and eye-witness accounts of the incident on the

Nueces River are conflicting. Some state that the wounded prisoners

were executed on the spot, not later in the day as related here. Accounts

also vary as to the number of participants in the fighting and the

number of killed and wounded on both sides. Even the very nature of

the tragic incident is in question. Confederate sympathizers consider

the fight a military action against a band of insurrectionists, but

many German residents of the Hill Country, focusing on the execution

of the wounded, regard the event as a massacre of the innocent. Nearly

all organized German resistance ceased when word of the “Battle of

the Nueces” spread, and many men fled to the safety of the frontier

where robbery, lynching and murder continued across the Hill

Country until the end of the war. After the war a monument to

the German dead was dedicated in Comfort.

|

|

Yet

another tragic Hill

Country incident occurred in July 1863, when eight well mounted,

well armed and well provisioned men and a young boy paused in the

small settlement of Bandera

on their journey from Williamson

County to Mexico. The men made no secret of their intent to ride

to Mexico to purchase prime ranch stock, and they all appeared quiet

and peaceful, paying for everything before they departed. Ironically,

two of the men were home on leave from Confederate service. Word of

the small party's presence was soon carried to nearby Camp

Verde, and a troop of 25 Confederates under the command of Major

W. J. Alexander, misinterpreting the men's ride to Mexico as an attempt

to avoid service in the war, started off in pursuit. In the pursuing

party were several men well known to the local settlers of Bandera,

but they all disappeared soon after the war.

Picking up the trail in Bandera,

Major Alexander and his men followed it a few miles beyond the settlement

of Hondo

to Squirrel Creek where they came upon the small party. Not knowing

they were being pursued, the Williamson

County men had just finished their noonday meal and were quietly

resting. The Confederates quickly surrounded the unsuspecting men

and Major Anderson called upon them to surrender, giving them his

word that if they would quietly submit, they would receive a fair

trial by court-martial at Camp

Verde. With little choice and with knowledge that they had committed

no crime, the eight men freely surrendered their arms. After being

relieved of the nearly $1,000 in cash they carried to purchase stock,

the prisoners were forced to saddle their horses and immediately start

back for Camp

Verde.

All went well until the following evening when some of the Confederates

suggested that the prisoners should be hung for attempting to flee

the state. Some historians have suggested that the $1,000 the Williamson

County men were carrying may have had a bearing on the decision

to hang them. Whether or not this was true, what may have well started

out as a prank quickly turned serious when Major Alexander turned

a blind eye to the situation and did nothing to put a stop to the

foul plan. A few Confederates refused to take part in the hanging

and chose to mount up and ride out, but the others marched the prisoners

a short distance from camp to a suitable live oak where they were

hung one by one.

A noose was quickly tied at the end of a horse hair rope and tossed

over the limb of the tree. Each of the Williamson

County men died by strangulation, being slowly drawn off their

feet until they choked to death. When the first man was dead, he was

let down and the rope was cut, leaving the noose still about his neck.

A new noose was quickly fashioned and the next man was hauled up.

One of the victims begged to be shot, saying that he much preferred

that manner of death to being slowly strangled. A Confederate complied

by firing a rifle at the prisoner, but he fell only wounded. Another

Confederate then shoved the muzzle of his rifle against the prisoner's

chest and pulled the trigger. He had mistakenly left the ramrod in

the weapon and it went through the prisoner, pinning his body to the

ground. When the bodies were discovered the next day, the ramrod was

mistaken for an arrow and at first the killings were blamed on Indians.

The young boy was said to have escaped, but he was never heard from

again. |

|

After the war,

the atrocity was remembered and the incident was referred to a military

tribunal. Major Alexander and his men were eventually indicted for

murder, but no one was ever arrested or tried for the crime. Today,

only the hanging tree, a fence and a simple tombstone inscribed with

the names of the eight Williamson

County men who lie beneath the tree in a common grave mark the

site of the heinous crime. Below the names, the tombstone reads" "Remember,

friends, as you pass by, as you are now, so once was I. As I am now,

you soon will be; prepare for death and follow me."

The

Gainesville-Sherman

area north of Dallas was

another center of dissent and was also perceived by some as a scene

of tragedy. The Butterfield Overland Mail route that began in St.

Louis ran through Gainesville

and brought many new settlers into Cooke

County from the upper South and the Midwest. By the start of the

war, fewer than 10 percent of the area households owned slaves. As

unrest over secession and the onslaught of the war grew, the slaveholders

increasingly feared the influence of the newcomers, and in the summer

of 1860 several slaves and a Northern Methodist minister were lynched

on suspicion of launching an uprising. When Cooke

County and a few other surrounding northern counties voted heavily

against secession, the slave holders believed their fears were justified.

In April 1862, the new Conscription Act gave rise to the first actual

opposition to the Confederate government in Cooke

County. A provision of the draft law exempting large slaveholders

from conscription angered many people who believed that since the

slaveholders were the cause of the war in the first place, they should

be among the first called to service. In an act of protest, a group

of thirty men signed a petition and sent it to Richmond. When word

of the petition reached Gainesville,

the local militia commander General William Hudson exiled the leader

of the group, but the other members began to organize a Union League.

Not many men joined the league and the effort was unorganized, but

rumors began to spread of a membership of more than 1700 and plans

to attack the local militia arsenal. |

|

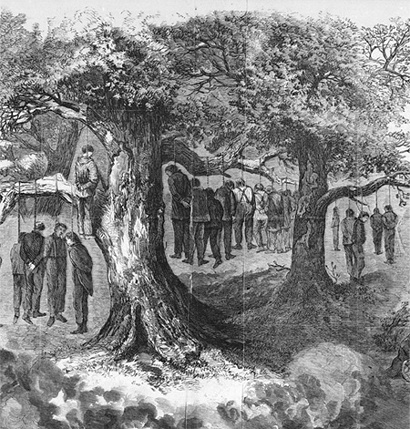

Hanging of Union

Men in Gainesville

From

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.

Prints and Photographs Collection 1993/202-5-4.

Texas State Library & Archives Commission |

|

On the morning

of October 1, state troops under the command of Colonel James G.

Bourland, a slaveholder, arrested 150 men in Gainesville.

With the assistance of Colonel William C. Young another slave owner

who was home on sick leave from the 11th Texas Cavalry, Bourland

organized a hasty “citizen’s court” of twelve jurors, seven of which

were also slaveholders. On a majority vote, the jury condemned seven

influential Unionists, but the angry mob was impatient and lynched

fourteen more men without the benefit of a trial. Things got even

worse for the Unionists the following week when an unknown assassin

killed Colonel Young. Nineteen more Unionists were quickly convicted

and hung. Their execution was supervised by the Colonel’s son.

|

|

|

Postwar

portrait of Jefferson Davis by Daniel Huntington

Wikimedia Commons |

|

Texans in general

and every newspaper in Texas celebrated the hangings. The Unionists

were compared to traitors and common thieves and branded as in league

with Kansas abolitionists and the Lincoln Administration. Texas

Governor Francis Lubbock, known to all as an ardent secessionist,

lauded the actions taken by the citizens of Gainesville.

However, not all southerners were pleased with the hangings. President

Jefferson Davis was so embarrassed that he withdrew his enquiry

into a similar incident involving Union soldiers in Missouri. Davis

also relieved General Paul Octave Hebert the military commander

of Texas for abusing the concept of martial law and replaced him

with General John Bankhead Magruder.

|

Hanging and Flogging

in Gainesville

From

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.

Prints and Photographs Collection 1993/202-5-6.

Texas State Library & Archives Commission |

The hangings

in Gainesville

were not the end of the violence or the dissent in Texas. Many Unionists

fled to the North, to Mexico or to California, and the ones who remained

in Texas did their best to keep a low profile, although that did not

always keep them safe. Captain Jim Young continued his pursuit of

revenge when he killed E. Junius Foster for applauding his father’s

death and tracked down Dan Welch, the man he accused of his Father’s

assassination. Young returned Welch to Cooke

County and had him whipped and lynched by a few of the family

slaves. A company of north Texas Confederate soldiers serving in Arkansas

nearly mutinied when they got word of the hangings, but their commander

General Joseph Shelby managed to diffuse the situation. Several of

the soldiers later deserted and returned home, but Shelby's actions

had prevented a mass attack on Gainesville.

However, ill feelings over the incident would continue to simmer until

the end of the war.

© Jeffery

Robenalt

"A Glimpse of Texas Past"

May 1,

2013 Column

jeffrobenalt@yahoo.com

References

› |

References

for "Dissention and the Draft in Civil War Texas"

|

|

Sam Hanna Acheson

and Julia Ann Hudson O'Connell, eds., George Washington Diamond's

Account of the Great Hanging at Gainesville, 1862 (Austin: Texas

State Historical Association, 1963).

Walter F. Buenger,

Secession and the Union in Texas (Austin: University of Texas

Press, 1984).

L.D. Clark,

A Bright Tragic Thing (El Paso: Cinco Punto Press, 1992).

Claude Elliot,

"Union Sentiment in Texas, 1861-1865," Southwestern Historical

Quarterly, 50:4 (April 1947).

Robert Pattison

Felgar, Texas in the War for Southern Independence, 1861-1865

(Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas, 1935).

Richard B.

McCaslin, "GREAT HANGING AT GAINESVILLE," Handbook of Texas

Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jig01),

accessed December 19, 2012. Published by the Texas State Historical

Association.

Stanley S.

McGowen, "Battle or Massacre?: The Incident on the Nueces, August

10, 1862," Published in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly,

Vol. 104, July 2000-April 2001.

James Smallwood,

"Disaffection in Confederate Texas: The Great Hanging at Gainesville,"

Civil War History 22 (December 1976).

Rodman L. Underwood,

Death on the Nueces: German Texans Treve der Union (Austin,

Eakin Press, 2002).

|

|

|